In the wake of hurricanes, as the deluge recedes, regulators see a rising flood of complaints about price gouging for necessities such as water and gas. And despite contrary opinions from some economists, 34 states have anti-gouging laws on the books. Even if there’s no law, people expect a retailer to feel bad about charging a different price to someone in a situation of desperate scarcity in a way that they don’t feel bad about a Black Friday sale, senior or student discount, coupons, and other ways to practice subtler price discrimination. But does the same thing apply when a business is 100% reliant on one technology provider?

We’ve always known that there is price discrimination in technology services. Larger customers or those with a marketable brand get a scale discount. Those who shop around, negotiate, and hire advisors, do better than those that just go with a known brand and trust the sales guy when he says he’s cutting his own throat to get this special deal. Anchor tenants that put their trust in a new service or co-lo are rewarded relative to later adopters; as are those who commit for a longer term.

There are also times when the scale, time, deal term, and all other facets of the deal are the same, but the prices are very different based on one thing and one thing only – whether the customer is “captive” and cannot switch to another service. Maybe the more egalitarian blockchain networks will have better governance and value exchange in the coming age of decentralization.

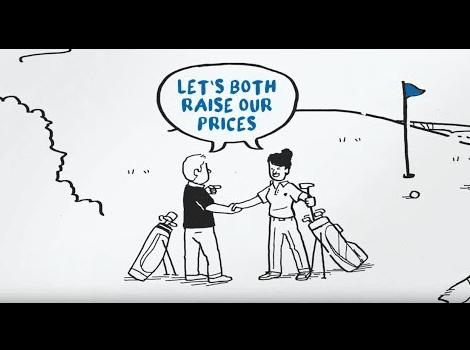

Next generation networks like EOS and Ripple may more fairly change for their services. While everyone has the right to make a profit, all boats should somewhat rise to stay healthy. Net Neutrality does the opposite and will persecute our access to certain informations at certain qualities. That’s why anti monopoly laws are important. In an extreme adverse example, the price of epipens led to the CEO going to prison.

Sometimes it’s due to a strategic relationship; organizational knowledge at the provider that’s hard to transfer; custom code to adapt to a specific CDN, etc. – difficult but not impossible to overcome obstacles. But a recent survey we did on low latency hosting (still open if you’re interested in participating and getting an aggregate of the results) showed that the gap is perhaps most glaring when the constraint is physics – latency constrained by the speed of light.

When a financial services client is in a specific co-lo building or campus because its usage scenario is low latency trading, its pricing can be 34%-75% higher than another financial services firm that’s buying the same amount in the exact same location but doesn’t care about those cross-connects as much; to say nothing of a client in online retail that just picked it for convenience to their offices. Same size, same timing, same skilled sourcing professionals. The only difference is captivity. But is that gouging?

Of course there are layers of salesmanship to help hosting provider execs avoid facing the question – and the lack of transparency in non-cloud IT infrastructure markets can allow them to get away with it. Just like some politicians focus on the source of the leak rather than the wrongdoing the leak exposed, there is brandishing of NDAs and demands to know sources when we expose the difference. But what if the secret is out? Is there a reasonable defense to say “yes, we charge you 50% more because you can’t go anywhere; just say thanks we’re not going the Martin Shkreli route and jacking it up by a factor of 56x”?

To some, the reasonable answer is in the concept of value-based pricing (as opposed to effort-based pricing) – if a low latency financial hub hosting service is more critical to a business function, it deserves a higher reward than the same space being used as just another co-lo. After all, we at RampRate charge more for saving someone $10M than for saving $1M even though our effort can often be similar. But still, no buyer we talk to is convinced that an identical service to an identical customer should be priced differently just based on their ability to switch.

So what do you think? Is price discrimination based on lack of alternatives justifiable? Would you support it openly, just as the economists opposing anti-price gouging laws do? Or do you think it’s an unethical practice that will die out if it comes out of the shadows?